- Zika Risk in U.S. States: Widespread or Limited? The White House Hijacks a Key CDC Message to Attack Republicans; Public Health Officials and Reporters Mostly Go Along by Jody Lanard and Peter M. Sandman – June 16, 2016

- Zika Rumors by Peter M. Sandman and Jody Lanard – February 22, 2016

- Zika Risk Communication: WHO and CDC Are Doing a Mostly Excellent Job So Far by Peter M. Sandman and Jody Lanard – February 3, 2016

Since February 3 when we posted our notes on “Zika Risk Communication: WHO and CDC Are Doing a Mostly Excellent Job So Far,” a few developments have prompted us to want to comment further. Rather than add more afterthought “boxes” – there are four already – we decided to create a new document with our new comments. We’re posting our first batch of such comments on February 16. We may or may not find more we consider worth adding in the weeks ahead.

Aside from the light they may shed on Zika risk communication itself, we also intend some of these comments as concrete illustrations of important generic risk communication principles and strategies. We hope interested readers will generalize the guidance to other infectious disease outbreaks and beyond.

Posted February 16

1. Zika test prioritizing may not be much of an issue fairly soon.

When we posted our notes on February 3, CDC was recommending testing only for women who had traveled to Zika-affected places while pregnant and had experienced Zika symptoms. But on February 5, CDC broadened its recommendation to include asymptomatic pregnant women returning from Zika-affected places:Updated guidelines include a new recommendation to offer serologic testing to asymptomatic pregnant women (women who do not report clinical illness consistent with Zika virus disease) who have traveled to areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission. Testing can be offered 2 – 12 weeks after pregnant women return from travel.

Of course the recommendation applies also to pregnant women who reside in Zika-affected places such as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. And when some Zika transmission occurs in the southern states, as is likely, the recommendation will presumably be extended to pregnant women in affected places in the continental U.S. as well.

CDC has emphasized that it is working hard to increase the availability of Zika test kits. It seems likely that the list of groups recommended for testing will grow to include pregnant women whose male partners have traveled to Zika-affected places, male travelers whose partners are pregnant, and women travelers who aren’t pregnant but are trying to get pregnant or at risk of getting pregnant (that is, not using birth control).

CDC has explicitly pointed out that its testing recommendations will probably change as new information emerges. A February 12 CDC update noted:

At this time, testing of men for the purpose of assessing risk for sexual transmission is not recommended. As we learn more about the incidence and duration of seminal shedding from infected men and the utility and availability of testing in this context, recommendations to prevent sexual transmission of Zika virus will be updated.

This is excellent anticipatory guidance ![]() , a good risk communication strategy. It helps people understand why recommendations may change, and reduces the chance that people will misperceive future changes as evidence of prior mistakes.

, a good risk communication strategy. It helps people understand why recommendations may change, and reduces the chance that people will misperceive future changes as evidence of prior mistakes.

In another example of good anticipatory guidance, CDC head Tom Frieden warned on February 5 that “Not everyone who wants to get a test will be able to get it,” adding that the agency was “working as fast as we can to increase the availability of testing.”

In the same press briefing, Frieden also deployed another good risk communication strategy, expressing wishes: “We wish more tests were available,” he said. “Our laboratories are literally working around the clock to get test kits out.”

After 9/11, when we were helping CDC develop a risk communication training program ![]() , we outlined some of the ways that expressing wishes can humanize technical information and help build a relationship with an anxious public.

, we outlined some of the ways that expressing wishes can humanize technical information and help build a relationship with an anxious public.

Despite Frieden’s warning and wishes, so far we haven’t seen a huge number of complaints about people being turned down or kept waiting for a Zika test. In fact we have seen a total of one such complaint, a cranky first-person article by a non-pregnant CNN reporter who returned from Costa Rica with symptoms that didn’t sound anything like Zika. She reported in tick-tock detail her failure to convince anyone to give her a Zika test.There are several benefits to expressing wishes. First, it humanizes you – you have wishes! Technical people may confuse sounding professional with sounding unconcerned and inhuman; at the extremes, an expert can sound enthusiastic and upbeat about what for everyone else is tragic – but the more common error is to sound matter-of-fact. Trust and learning are higher when you reveal your humanity.

Second, expressing wishes is a way to acknowledge your failings gently but still self-critically. When you say you wish you had done X, you aren’t quite defining your failure to do X as culpable, requiring contrition. But you are regretting the failure.

Third and most important, you can express your audience’s wishes. If your audience is aware of the wish – the wish that your answers were more definitive, for example – this shows that you share it, that you understand the downside of the news you are imparting.

If no testing logjam develops, obviously, explicit prioritization categories won’t be needed. And our insistence that women contemplating abortion should have priority over women for whom abortion is not an option will be moot.

Meanwhile, the growing Zika-microcephaly-abortion controversy provides evidence – if anyone needed evidence – that CDC was politically wise not to recommend prioritizing women considering abortions over women who had ruled out that possibility. Dozens of articles have addressed the question of whether the risk of Zika-related birth defects will, or should, alter the anti-abortion stands of the Catholic Church and various Latin American governments. And testifying in Congress on behalf of an emergency appropriation to fight Zika in the U.S., Frieden faced aggressive questioning about whether any of the money would be used to help women get abortions. Just imagine the questioning, and the fate of the appropriation request, if CDC had gone on record that women considering abortion should go to the head of the Zika testing line.

To its credit, WHO has unequivocally stated that “Women who wish to terminate a pregnancy due to a fear of microcephaly should have access to safe abortion services to the full extent of the law.” Abortion is legal in the U.S. But it’s hard to picture CDC making that statement.

2. Officials would be wise to acknowledge more aggressively the fizzle scenario.

WHO, CDC, and experts around the world agree that the evidence linking Zika to microcephaly keeps getting stronger. Most official sources continue to acknowledge that the evidence still isn’t conclusive. But they have sounded a lot more confident since two February 10 articles in the New England Journal of Medicine and in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, both of which reported finding Zika virus in the damaged brains of newborns or fetuses whose mothers had been infected during pregnancy.

On the other hand, we have read scads of journal articles, mass media articles, and Internet posts pointing to flaws in the evidence about the link. Some of the authors are scoffers, arguing that the Zika-microcephaly link is hype (aimed, perhaps, at building the case for yet another vaccine). Some are conspiracy-mongers. But most of the critiques are quite moderate and reasonable; many concede that the link is probably real but argue that it may be much less common than the initial data from Brazil suggested.

Three points stand out in these commentaries:

- Brazil’s pre-Zika estimates of microcephaly incidence were very low – lower than estimates from many other countries and lower than is credible. This under-reporting is entirely understandable given the difficulty of surveillance. Nonetheless, it matters that the reported increase in Brazilian microcephaly cases was based on an unrealistically low baseline number.

- Brazil’s post-Zika estimates of microcephaly incidence were very high, as increasing concern led doctors and hospitals to cast a wide net. This over-reporting is also understandable, even desirable. But it is also misleading. Follow-up investigations of a subset of the reported cases of suspected microcephaly found that many weren’t microcephaly at all, and many others were attributable to causes other than Zika, such as maternal alcoholism.

- Some countries – most notably Colombia – have reported other Zika complications such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, but not microcephaly. Since Zika seems to have reached Colombia several months later than Brazil, it is possible that cases of Zika-related microcephaly will become more apparent in Colombia in the coming weeks and months. But at least some investigators say they are intrigued that Colombia hasn’t seen these cases already, and are looking into possible reasons why.

The official position that the Zika-microcephaly link is almost certainly real is not incompatible with the view that the link is almost certainly smaller than it looked at first. Both are probably true.

We have been here before. In 2009, the initial data from Mexico made the emerging H1N1 flu pandemic look horrifically virulent. Officials quite rightly responded quickly and strongly. But as weeks and months passed and better data became available, it gradually became clear that the pandemic was relatively mild – still deadly enough to justify vaccination and other precautions, but in the end less deadly than many annual flu seasons. WHO in particular came under attack for having overreacted to the pandemic (an unfair criticism in our view) and for having failed to recalibrate its claims as evidence mounted that the pandemic wasn’t as severe as it had looked (a much fairer criticism).

From a risk communication perspective, what’s unfortunate here is that officials are focusing too narrowly on the evidence that the Zika-microcephaly link is real, mostly neglecting the open question of how big or small a risk it may turn out to be in terms of frequency. We understand the many reasons why there is not yet a reliable quantitative estimate of the frequency with which Zika infection during pregnancy – or at various stages of pregnancy – leads to microcephaly or other profound birth defects.

But under these conditions of uncertainty, we believe officials should more forcefully state four things:

- They should discuss the main points made by the skeptics, and acknowledge (when true) that these points have some validity – and thus that the percentage of microcephalic babies of Zika-infected mothers is likely to be lower than it looked at first … maybe only a little lower, maybe a lot lower.

- They should explain why they don’t yet have an estimate of the risk to babies of Zika-infected mothers, empathize with pregnant women who are desperate for such an estimate, say they wish they had one, and tell what they are doing to come up with one.

- They should point out that in the meantime they are acting as if the Zika-microcephaly link were strong – as if the risk to babies of Zika-infected mothers were high – all the while hoping the link will turn out much weaker and the risk much lower than their worst case scenario.

- They should urge the public to do likewise, to consider the Zika microcephaly risk extremely serious until proven otherwise (in the excellent words of WHO’s Chris Dye, “guilty until proven innocent”). So the recommended precautions – DEET, mosquito control, testing of pregnant women, etc. – should be implemented with zeal, despite the real possibility that we will turn out to have overreacted.

Protecting the public from Zika is a higher priority than maintaining or enhancing the credibility of public health agencies like CDC and WHO. So the recommended precautions to reduce the risk to the babies of pregnant women deserve more emphasis than the possibility that the risk may turn out small and the precautions excessive. But the best reputational outcome is to warn people about the possible risk of Zika while protecting credibility if the risk turns out overblown. That’s part of why we think the fizzle scenario deserves more official attention than it has received thus far.

We see at least three reasons why public health officials should acknowledge the validity of the skeptics’ valid arguments.

First and foremost, the public – especially anxious pregnant women who have spent time in Zika-affected places – deserves to hear both halves of the story from the same official sources. It is disorienting, confusing, and mistrust-arousing to hear only the alarming side from officials, and then to read news stories pointing out reassuring facts that officials haven’t addressed. (We hasten to add that the skeptics have an even greater obligation to acknowledge the alarming side of the story, to concede that even if the Zika-microcephaly link turns out smaller than it initially looked, it is almost certainly real and may well deserve the precautionary attention it is getting.)

Second, the skeptics deserve official validation of their valid claims (not their invalid claims, of course). One of the things that turn skeptics into scoffers is when officials seem to be stonewalling.

And third, the reputation of public health is, as always, in play. It will be wonderful news if Zika turns out to cause severe birth defects only occasionally – perhaps, as some have hypothesized, only if the mother has been previously infected with a particular strain of dengue. But there will be other health threats in years to come, and not all of them will turn out less dangerous than they initially looked. A reputation for crying wolf will make it harder for public health agencies to guide the public through these future threats.

3. Officials keep saying they’re convinced that mosquitoes are the main way Zika is transmitted, not sex – which makes their fervent recommendations about sexual precautions sound a bit extreme.

There is evidence – not much, but enough – that Zika can survive for some time in the semen of a man who has been infected, and that he can transmit it to a sexual partner. But all the experts seem to agree that sexual transmission is rare, the exception not the rule. In the vast majority of cases, they all say, Zika is transmitted when a mosquito bites an infected person, incubates the Zika virus, and then bites a previously uninfected person.

We’re not questioning this expert consensus. But we do have a little trouble reconciling it with the strong emphasis on sexual transmission in official communications.

On February 5, CDC issued “Interim Guidelines for Prevention of Transmission of Zika Virus.” These guidelines were the top focus of a February 5 CDC media statement and the sole topic of a February 5 CDC Q&A. Much of CDC’s February 5 Zika press briefing also focused on sexual transmission. And on February 12, CDC issued an updated version of the “Interim Guidelines.”

The CDC’s key recommendations: Male travelers from Zika-affected places shouldn’t have unprotected sex (including oral and anal sex) with a pregnant woman for the woman’s entire pregnancy. They should consider not having unprotected sex with anybody, especially with a woman who might be or might get pregnant. And people – especially women who are pregnant or might be or might get pregnant – shouldn’t have unprotected sex with men whose travel history they don’t know.

This advice aroused considerable opposition. Not surprisingly, many critics called it unrealistic. More surprisingly (to us), some called it anti-woman. We don’t see any sign that CDC’s potentially hard-to-buy advice about sexual precautions undermined its much more important advice about mosquito precautions, though that is a possibility. At a minimum, it comes across as pretty extreme advice for a transmission route that is considered rare.

We certainly see the case for advising that pregnant women shouldn’t have unprotected sex with men who traveled to Zika-affected places and had Zika symptoms. But the idea that a woman who just might get pregnant shouldn’t have unprotected sex with a man who just might have taken a trip to Brazil? Even though the goal is obviously good – to reduce even the remote chance of an infected fetus – that comes across as a bit over-the-top.

Consider also how WHO has handled these two transmission routes: mosquitoes and sex.

Our February 3 notes on “Zika Risk Communication” included a box entitled “Science-driven travel advice versus taboo-driven travel advice,” in which we criticized WHO for refusing to advise pregnant women not to travel to Zika-affected places. We concluded that “as long as the Zika-microcephaly link looks convincing, any organization that doesn’t urge pregnant travelers to stay away can hardly call itself ‘science-based.’”

On February 12, WHO made a welcome concession. Its revised guidance says that pregnant women should “consider delaying travel to any area where locally acquired Zika infection is occurring.” In a press conference ![]() accompanying the new recommendation, WHO officials insisted that the new advice didn’t amount to a travel restriction – presumably because pregnant women weren’t ordered not to go, weren’t even urged not to go; they were only urged to consider not going. We’re okay with the fig leaf; it’s the new advice that matters.

accompanying the new recommendation, WHO officials insisted that the new advice didn’t amount to a travel restriction – presumably because pregnant women weren’t ordered not to go, weren’t even urged not to go; they were only urged to consider not going. We’re okay with the fig leaf; it’s the new advice that matters.

WHO said the new advice was “based on the latest evidence that Zika virus infection during pregnancy may be linked to microcephaly in newborns.” The previous evidence, apparently, hadn’t been convincing enough.

Now consider these three paragraphs from the same revised guidance document:

Zika virus is spread by mosquitoes, and not by person-to-person contact, though a small number of cases of sexual transmission have been documented.

Zika has been found in human semen. Two reports have described cases where Zika has been transmitted from one person to another through sexual contact.

Until more is known about the risk of sexual transmission, all men and women returning from an area where Zika is circulating – especially pregnant women and their partners – should practice safe sex, including through the correct and consistent use of condoms.

In other words, Zika is transmitted mostly via mosquitoes; only two reports have described sexual transmission. Therefore, pregnant women should think about maybe not traveling to Zika-affected places themselves. But they definitely shouldn’t have unprotected sex with a man who has traveled to Zika-affected places. In fact, anybody who has traveled to Zika-affected places definitely shouldn’t have unprotected sex with anybody else. Consider changing your travel plans. Definitely change your sexual habits.

What kind of sense does this make, given the universal conviction that mosquitoes pose a much greater Zika risk to pregnant women than unprotected sex? It helps to remember that, Zika aside, WHO has a very positive attitude toward condoms and a very negative attitude toward travel advisories and travel restrictions.

We are still trying to find out what internal policies WHO has developed for its own pregnant staff members outside of Zika-affected areas, in terms of possible postings to such areas.

4. A Zika quarantine is almost certainly a bad idea, at least under current circumstances – but that’s no excuse for U.S. public health professionals making irrational arguments against it.

In a February 6 debate among Republican Presidential candidates, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie (who has since abandoned the race) was asked whether there was any scenario “where you would quarantine people traveling back from Brazil to prevent the spread [of Zika] in the United States.” He answered, “You bet I would,” and went on to defend his controversial 2014 Ebola quarantine policy.

The exchange led to several articles, all of them insistent that a Zika quarantine would be impractical and useless. With neither a rapid test nor an effective vaccine to reduce the number of people to be quarantined, we agree that a Zika quarantine is impractical. Millions of people would need to be quarantined, year after year after year assuming Zika becomes endemic in parts of the world.

But we see no sense whatever in the claim that even if – hypothetically – a practical way to manage a Zika quarantine could be found, it would still be useless. If it could work, which we very much doubt, how could it be useless?

Consider this excerpt from a February 9 article by Laurie Garrett, a global health policy expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, entitled “A Plea to Presidential Candidate Christie: Please Stop Talking About Zika”:

Gov. Christie, the Zika virus is spread by mosquitoes, which you should “quarantine” or obliterate to protect the good people of New Jersey. But Zika is rarely, if ever, spread from person-to-person, so quarantining infected people will do nothing to stem a Zika outbreak. Yes, there is evidence that pregnant women can pass the virus though the placenta to their fetus, and, in three cases, infected men may have passed the virus to a sexual partner. But a tough guy like you knows the enemy when you see it, right? And the enemy is Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which are found in the Garden State every summer….

Moreover, Mr. Governor, you have already had a person infected with Zika in your state – a traveler from Colombia, visiting Bergen County in mid-January. You did not order that traveler placed in quarantine or housed à la Hickox in a parking lot-nested tent.

Garrett’s reference in the second paragraph is to New Jersey’s isolation of returning Ebola volunteer Kaci Hickox after she registered a fever at Newark Airport. Much of Garrett’s article, in fact, is an attack on New Jersey’s Ebola quarantine policy. We have had previous occasion to note the unreasoning and uncivil opposition of public health professionals to the genuinely debatable policy of Ebola quarantine. We won’t repeat ourselves here. If you’re interested, see “COMMENTARY: When the Next Shoe Drops – Ebola Crisis Communication Lessons from October” and “Ebola in the U.S. (So Far): The Public Health Establishment and the Quarantine Debate.”

We feel like we’re watching the same script recycled for a new pathogen. Garrett’s sarcastic tone notwithstanding, mosquitoes are not the only “enemy” when it comes to Zika. Humans are the host for Zika virus, and mosquitoes are the vector. The goal of any human quarantine is to prevent infected or possibly infected people from transmitting a disease to others – whether they do so directly or via mosquito. Of course in January, when New Jersey has no mosquitoes, a Zika quarantine would indeed be useless. But as Garrett herself points out, it might be a different story in a Jersey summer, since Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are occasionally found there in the summertime.

In a February 7 Scientific American article entitled “Why We Shouldn’t Quarantine Travelers Because of Zika,” epidemiologist Tom Talbot of Vanderbilt University Medical Center says that “the virus does not spread in a way that makes quarantine something that should be considered.” Talbot’s point, like Garrett’s, seems to be that Zika is spread via mosquitoes, not human-to-human. We don’t see the point. The purpose of a Zika quarantine would be to prevent contact between Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and people who might be infected with Zika. If no mosquitoes capable of transmitting Zika have access to people infected with Zika, no mosquito-borne domestic outbreak is possible.

Again, please note that we are not remotely advocating a Zika quarantine.

But in the realm of mosquito-transmitted diseases, quarantines continue to play a well-established role, legal under the International Health Regulations, in many nations’ health laws. Like Zika, the yellow fever virus is a flavivirus transmitted by Aedes aegypti. If you have recently been in a country where yellow fever is circulating, and arrive without a current International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP) against yellow fever, numerous countries will forbid your entry, or vaccinate you on the spot, or quarantine you for six days. Some countries have these same stringent yellow fever rules for all incoming travelers, even those in transit, regardless of what countries they have been in recently.

Other public health officials and experts joined the consensus against Zika quarantine in a February 8 Mother Jones article entitled “Here’s Why Chris Christie’s Zika Quarantines Would Be Pointless.” Dean Blumberg, chief of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of California-Davis, put it this way: “The vast majority of transmissions are from mosquito bites, and most of the country doesn’t have the [Aedes aegypti] mosquito in high concentrations. So I don’t think [a quarantine] is necessary or would be beneficial in any way.”

We get it that a Zika quarantine in Minnesota (or in New Jersey in winter) would be pointless. We get it that a Zika quarantine in Puerto Rico, where the virus is already circulating, would be futile. But what would be Blumberg’s objection to Zika quarantines in parts of the country where Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are present but Zika isn’t yet circulating? Our guess is that his objection comes down to the impracticality of such a quarantine, not the lack of potential benefit if such a quarantine were indeed practical.

If it is sensible to try to keep uninfected people from getting bitten by Zika-competent mosquitoes so they won’t catch the disease, why isn’t it also sensible to try to keep infected people from getting bitten so they won’t spread it? Obviously, it is sensible. The question is whether any sort of quarantine can achieve this objective in a practical way. Zika quarantine is almost certainly a bad idea because it is too hard and too costly and too internationally damaging and too unlikely to work – not because Zika is transmitted via mosquitoes rather than human-to-human. It might not be a bad idea if ways could be found around those caveats. (We cannot think of any such ways, at this point.)

The Scientific American article concludes this way:

Although the mosquitoes that are biologically capable of transmitting the virus already live in the U.S., primarily on the Gulf Coast, the same mosquitoes are also capable of passing on dengue and chikungunya and there have not been large outbreaks of either illness despite the fact that travelers coming to the U.S. with symptoms have not been quarantined. That suggests the only thing that needs quarantine right now is fearful claims that sequestering travelers from more than 30 countries and territories with the virus is necessary.

We agree that there probably won’t be big U.S. Zika outbreaks. We agree that quarantining travelers from 30+ countries for a week or two forever looks impractical and likely to do more harm than letting them in to launch small local Zika (and dengue and chikungunya) outbreaks. But letting them in is deciding it’s okay not to try that way to reduce the number of small local outbreaks. We’d like to see public health experts regretting aloud that they can’t think of any practical way to implement an effective Zika quarantine, instead of attacking anyone who dares to suggest that it might make sense to think about it.

What bothers us as risk communication experts is the contempt and dripping disdain routinely heaped on those who propose – or even just want to consider – precautions beyond current official recommendations. The vitriolic put-downs aimed at such people are not the kind of risk communication likely to win them over, nor to win over those who are not yet sure whom to trust or what to think.

One more time: We are not advocating on behalf of Zika quarantine. But the case against Zika quarantine is not strengthened by fallacious, tendentious, condescending, contemptuous arguments. (For a similar example of experts combining sound arguments with fallacious, tendentious, condescending, and contemptuous arguments against a controversial precaution, see “The Dilemma of Personal Tamiflu Stockpiling.”)

5. Lots of public health professionals and media commentators seem to think that Americans are panicking about Zika. We don’t see any signs of it.

In our original post on “Zika Risk Communication,” we wrote about the Zika adjustment reaction and the reasons why it’s a mistake to call it panic.

Not surprisingly, that mistake is widespread.

We have scores of articles in our files in which public health professionals, journalists, and others refer in passing to Zika panic, as a phenomenon too obvious to require evidence. In an article comparing Zika to rubella, for example, pioneering vaccinologist Stanley Plotkin (one of Jody’s greatly admired medical school professors) notes: “If we had a vaccine against Zika, we could be protecting women.” But without it, he says, “you have the kind of panic you have now.” An article on the economic repercussions of Zika starts out obliquely by noting that Zika has been linked to birth defects “and there’s nothing like the prospect of a generation maimed to trigger panic.” And so on, ad nauseam.

Below are some developed world Zika articles and editorials with “panic” in their titles. As is clear from the titles themselves, many of these articles and editorials are about why Zika panic isn’t warranted, or isn’t warranted yet. Few if any suggest that Zika panic might not actually be happening.

- Dr. Brownstein on Zika Virus: No Panic Needed (February 13)

- Is the Zika Panic Overblown? (February 9)

- 3 reasons not to panic over the Zika virus (February 9)

- Obama seeks funds to fight Zika; sees no cause for panic (February 8)

- Let’s not panic about Zika: We still don’t know how dangerous the mosquito-borne virus really is (February 6)

- Zika: Why we shouldn’t panic (February 5)

- No need to panic over Zika (February 5)

- As Florida Gov. Rick Scott raises the alarm on Zika virus, Tampa Bay mosquito control officials say don’t panic yet (February 4)

- The Guardian view on Zika fever: panic won’t help us (January 29)

- Disease expert on Zika: Americans shouldn’t panic (January 29)

- The rare birth defect that’s triggering panic over the Zika virus, explained (January 28)

So is there any actual evidence of Zika panic in the U.S.? As far as we can tell, no.

So far, in fact, Americans seem less concerned than they were about Ebola – and we argued again and again that the Ebola adjustment reaction in the U.S. wasn’t panic either. (For example, listen to this radio interview with Jody.) At least there were a few actual anecdotes about a very few citizens’ Ebola overreactions, reiterated endlessly in social and mainstream media as if they were typical rather than outliers. We haven’t seen comparable anecdotes about Zika overreactions.

Of course that could change. There are several “firsts” yet to come with regard to Zika. Two in particular are likely to arouse additional public concern: the first documented case of local transmission in the continental U.S. (someone who caught Zika in the States from a mosquito in the States); and then, later, the first documented case of microcephaly in a baby born to a woman who caught Zika here. In addition to these predictable but upsetting moments, anything surprising will also arouse additional concern – for example, if other species of mosquito with a wider U.S. range are shown to be capable of transmitting Zika.

Assuming that “degree of concern” has something like a normal distribution, higher overall levels of concern are likely to yield larger numbers of genuine overreaction stories – outliers that can then be cited as evidence that the whole country is freaking out. In the age of Twitter, it has never been easier for reporters to find the most extreme reactions to anything. Unfortunately, we regularly see these extreme but rare reactions cited as evidence of widespread panic. Remember “HazMat Lady” during Ebola?

But we haven’t seen anything like that yet with Zika. If anything, Americans are taking Zika in stride. People are mainly interested, sometimes even fascinated; avid for more information; saddened by the endless photos of microcephalic babies; but not freaking out (all those headlines notwithstanding). Many pregnant women who have returned from trips to Zika-affected places are quite rightly worried. Most are doing exactly what CDC advises: seeking counsel and ultrasounds from their obstetricians. Many pregnant women who were considering trips to Zika-affected places are sensibly canceling their trips if they feel they can, and worriedly planning their mosquito-avoidance strategies if they feel they must go. Pretty much everybody else is looking on with more sympathy than fearfulness.

We wouldn’t consider it panic if millions of Americans were stocking up on DEET-containing mosquito repellants – but as far as we know no U.S. stores have reported selling out. We wouldn’t consider it panic if millions of southern Americans were obsessing over standing water in their yards and their neighborhoods – but as far as we know that’s not happening either. We wouldn’t consider it panic if there were loud citizen demands for more aggressive government mosquito-control programs – but while plenty of state and local governments are ramping up such programs, they are mostly doing so of their own volition, not in response to a anxious public.

We might very well consider it panic if millions of Americans were deciding to postpone plans to get pregnant just in case Zika ends up more prevalent in the continental U.S. than is expected. Some Latin American governments in places where Zika is circulating widely or expected to circulate widely have made that recommendation. There have been no reports of any such trend in the continental U.S.

So if Americans are panicking about Zika, then the meaning of the word “panic” has changed. Sometimes we think “panic” now means simply a sudden upsurge in people reading and tweeting about something new, fascinating, mysterious, and potentially scary, while going about their business and taking few if any special precautions (even recommended ones). If that’s the new definition of “panic,” then maybe Americans are panicking about Zika.

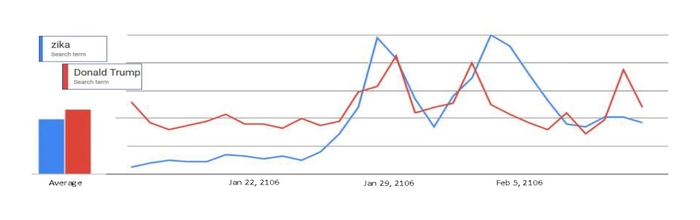

Or maybe not, even under that watered-down definition of “panic.” Here’s a Google Trends graph of Google searches in the U.S. for two terms, “Zika” (blue) and “Donald Trump” (red), from January 15 through February 11.

Two things stand out. First of all, Zika searches aren’t escalating. There have been two peaks so far, January 28 and February 3. Zika searches declined quickly from February 3 to February 7, and stayed low from February 7 to February 11. The second conclusion: If this is what panic looks like, then Americans are panicking about Donald Trump too.

Google Trends for “Zika” and “Donald Trump,” January 15 – February 11, 2016

All the above notwithstanding, it’s certainly true that Americans and American media are reacting more powerfully to Zika than they have reacted to two other mosquito-borne viruses that are occasionally imported into the continental U.S., where they cause limited local transmission: dengue and chikungunya.

Governments are reacting more powerfully too; CDC’s travel advice about dengue and chikungunya was much more muted than its warnings about Zika.

While neither dengue nor chikungunya is thought to cause birth defects, both are extremely painful. Dengue’s nickname is “breakbone fever,” for the joint pain it causes. Chikungunya’s name comes from a word said to mean “to become contorted” or “to bend upward” – a result of agonizing joint pain. Dengue sometimes morphs into dengue hemorrhagic fever, which can be deadly. Chikungunya patients often miss weeks or months of work.

During the explosive spread of chikungunya in the Americas in 2014 and 2015, there were more than 1.5 million suspected and confirmed cases. On some Caribbean islands, more than half the population came down with chikungunya in less than a year. Nonetheless, Caribbean tourism in 2014 increased ![]() 5.4 percent year on year. In 2015, “Visitor numbers to the Caribbean (+7.4 percent) and Central America (+7.1 percent) rose more than any other region” in the world. More than 1,000 U.S. travelers returned to the mainland with chikungunya.

5.4 percent year on year. In 2015, “Visitor numbers to the Caribbean (+7.4 percent) and Central America (+7.1 percent) rose more than any other region” in the world. More than 1,000 U.S. travelers returned to the mainland with chikungunya.

Since mid-September 2015, Hawaii has had 255 confirmed dengue cases, caused by local transmission. As far as we know, few travelers are canceling their Hawaiian vacations because of dengue, nor is CDC advising them to do so.

It’s not hard to see why. Both dengue and chikungunya are far more dangerous and vastly more painful to adults than Zika, and both are far more widespread. But neither raises the terrifying specter of microcephaly. And neither is as new and mysterious as Zika, as likely to pose unknown risks yet to be discovered.

We’re more inclined to see this gap as an underreaction to dengue and chikungunya than as an overreaction to Zika. If this underreaction is your yardstick, then Americans are indeed “overreacting” to Zika. But even by that yardstick, the U.S. reaction to Zika we have seen so far is composed of avid interest, fearful concern, empathic sadness, and fascination. It certainly is not panic.

- Zika Risk Communication: WHO and CDC Are Doing a Mostly Excellent Job So Far by Peter M. Sandman and Jody Lanard – February 3, 2016

- Zika Rumors by Peter M. Sandman and Jody Lanard – February 22, 2016

Copyright © 2016 by Peter M. Sandman and Jody Lanard