Warning others after an accident that they could have one too

| Name: | James |

| Field: | Public relations consultant |

| Date: | December 12, 2009 |

| Location: | Washington, U.S. |

comment:

I had a quick question on crisis communication. I’m hoping you can point me in the right direction.

One of our clients is a leading manufacturer and recently had an accident (explosion of secondary tank) at their production facility. Details are still emerging on the cause, but there is a potential that the accident could have been caused by a chemical reaction that is commonly used in the entire industry. As we move forward on communications strategies with them, we are evaluating if the company should take a stance and inform the entire industry of this risk, at the risk of drawing attention to a potentially fatal flaw in a commonly used system – obviously with positive and negative potential impacts to such a stance.

We are in the process of our due diligence/background research on such an approach (has it worked in the past, who else has done it, what are the pros/cons). Do you know of any other examples in which one industry player has made such an announcement that could have impacts on the entire industry?

Peter responds:

In my terms, your problem isn’t so much crisis communication. Your client had a crisis, a high-hazard, high-outrage situation. Now you’re trying to decide whether to do precaution advocacy – to warn others who may face the same high hazard but aren’t experiencing any outrage (concern) yet. And I surmise that you’re worried about whether doing so might arouse some outrage (anger) against your client for blowing the whistle. So it’s a hybrid.

I believe it is established best practice that when a company has an accident, and learns that the cause may be a problem that’s generic and could affect others in the industry, it should notify them in order to prevent additional accidents. A few examples at random:

- In the airline industry it is obligatory to do this sort of root cause analysis and make the results known to other airlines. Regulators routinely put their muscle behind this requirement. After X company has an accident (or even a false alarm) that reveals a specific generic problem, all other companies using the same aircraft are told about the problem and either required or urged to take appropriate action.

- In Canada, Maple Leaf Foods had a food poisoning outbreak in August 2008 that was traced to Listeria contamination in a food slicer. The slicer was constructed in a way that made a particular part hard to clean … and that part ended up harboring the Listeria. The company notified the manufacturer and other companies using the same slicer, and changes were made in the cleaning protocol for that piece of equipment. (Maple Leaf’s handling of its Listeria outbreak has been universally praised.)

- A client in Alaska sandblasted a huge industrial tank, and later picked up high measurements for asbestos inside the tank. It turns out the sandblasting medium (the sand, essentially) contained asbestos. The company immediately notified the manufacturer. When I lost contact with the case, it was considering whether it had a further obligation to notify product safety regulators and the public so that other users of that brand of sandblasting medium would be aware of the problem. I don’t know what it decided, but I know what I think it should have decided.

I’m not an attorney and don’t know the conditions under which a company would have a legal “duty to warn.” But as a risk communication professional, I am confident that the public would hold a company morally culpable if it withheld information about a potentially serious problem, and as a result people in other locations were hurt by the same problem. I think your client is likelier to incur outrage by not issuing such a warning than by issuing it.

Of course it’s important not to go beyond what you actually know. “Preliminary evidence suggests….” “Although we are not yet certain, we decided it was important to let people know what we have learned so far, in order to prevent possible future accidents elsewhere….” If a company reports the results of its investigation accurately, and acknowledges the possibility that further research may lead to different conclusions, it ought to be legally and reputationally safe from claims that it is defaming the manufacturer, damaging public confidence in the operations of competitors, or whatever.

The decision about how broadly to announce what you know (or think you know) may be a difficult one. Do you tell just the manufacturer? The manufacturer and other companies in the industry? Those plus the relevant regulator? Plus the unions representing potentially endangered employees? What about other companies’ shareholders and the general public?

In making these choices, your client should bear in mind that saying too little is a graver reputational risk than saying too much.

One other issue: It’s important that this information be framed in a way that sounds like the company is trying to warn others about a possible future accident, not trying to escape responsibility for its own past accident. The biggest reputational downside to releasing the information is the possibility of getting accused of trying to wriggle out from responsibility by suggesting that “everyone does it” and “we didn’t do anything wrong that led to our accident.”

You may be interested in the following two-part article from Industrial Safety and Hygiene News:

-

Talking about “What Happened”: Post-Event Risk Communication (Part 1)

- Talking about “What Happened”: Post-Event Risk Communication (Part 2)

Published in ISHN (Industrial Safety and Hygiene News), May 2005, pp. 19–20, and June 2005, pp. 36, 38

The first recommendation in Part 1 is “Tell everyone who should know.” That’s it in a nutshell.

What should we tell people about vaccination if the pandemic wave is ebbing?

| name: | K.M. | |

| Field: | State health policy and planning professional | |

| Date: | November 20, 2009 | |

| Location: | U.S. [state suppressed on request] |

comment:

People in my state health department are asking me what they should say in response to this question: Why get vaccinated when the pandemic H1N1 wave has passed?

Here's the response I drafted for them:

Be Transparent.

- It must be remembered that we are presently in our second wave of disease. The first wave occurred beginning in late April. We were one of the first states to report a confirmed case of H1N1. We are still subject to third and fourth waves of the virus. The more people that get vaccinated, the less chance that these waves will have as severe an impact.

- Summarize the actual impact so far and compare it to a regular flu season to illustrate that it is bad. The perception of people about how mild it is has been is counterproductive.… This will support the first point above.

- A lot of people are concerned about the vaccine for H1N1. So far…. (GIVE adverse event summary to this point in time.) H1N1 is as safe as seasonal vaccines and in fact is essentially manufactured in the same way they are. There is no need to fear this vaccine. This has been specifically noted as one of the reasons people were not going to get vaccinated. Address it up front.

- Get more people like _____ to get vaccinated. Perhaps have an event with highly respected and TRUSTED people who get vaccinated once priority populations are out of the fore. Let people see that others they know and trust are getting it. This will support the previous point also.

- Remind people that they also still need to get the seasonal vaccine. We have yet to move into the peak normal seasonal flu season. Get them both….

Any feedback would be appreciated.

Peter responds:

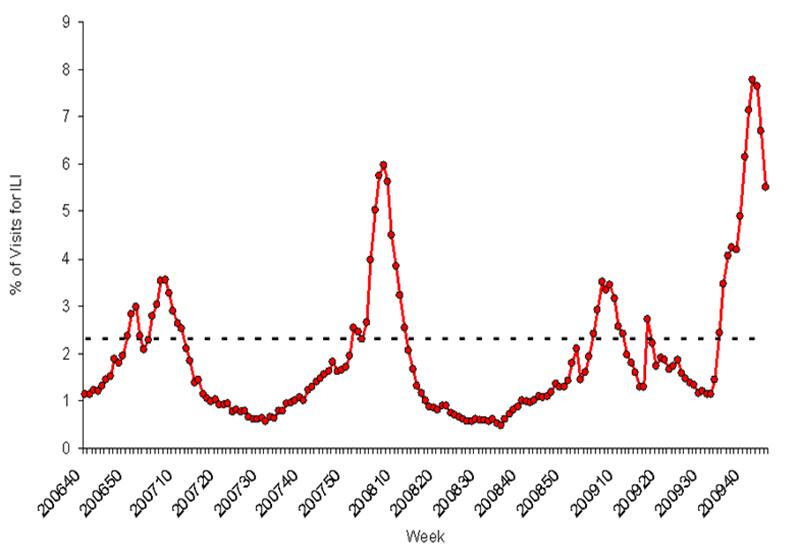

I admire your willingness to be transparent regarding the evidence that the second pandemic wave may be ebbing. As you know, that evidence (on a national level) isn’t unequivocal yet. CDC Director Tom Frieden testified before Congress on November 4 that he thought the wave was peaking and would probably ebb before we had enough vaccine, but then decided the patterns were too varied from state to state to justify such a prediction (yet) and backed off of it. The CDC’s weekly graph of the percentage of doctor visits that were for influenza-like illnesses is still very high, though it has declined significantly over the past three weeks.

So there are really two questions: What do you say now about the possibility that the pandemic wave is about to ebb? And what will you say in a few weeks if it becomes clear that the wave is in fact ebbing?

I agree with you that transparency will be the right response when the evidence is clear. I also think it would be best to warn people now that this may be occurring, rather than appearing to pivot on a dime a few weeks from now from “it’s awful” to “it’s almost over.”

Regarding your proposed answer, I agree that it’s important to ground that answer in uncertainty. Even when we become sure that the second wave is ebbing, we still won’t have a clue whether a third wave is coming. Nor will we know when it will come (if it comes) or what it will look like. It wouldn’t be shocking to see a third wave just weeks after the second … or not till spring … or not till next winter. It wouldn’t be shocking if the third wave came quickly, with little if any warning … or it could creep up on us slowly. Above all, we have no basis for predicting whether the third wave might be more virulent (perhaps even much more virulent) than the second; there’s no evidence of increasing virulence so far, but other pandemics (especially 1918) had later waves that were much more virulent than what had come before, so it’s certainly a possibility.

In the face of all that uncertainty, vaccination (when there’s ample vaccine) makes good sense.

Another important point to make that you didn’t make: People wrongly imagine that the crest of a wave is the end of that wave. In reality, it’s only halfway to the end. When a pandemic wave crests, roughly half the infections, hospitalizations, and deaths attributable to that wave are still to come. There will be plenty of people still getting sick as the second wave ebbs. Unless it ebbs very quickly indeed, some of those people could be protected by post-crest vaccination.

There are two things I don’t like about your proposed answer.

I don’t like your bald claim that the pandemic is “bad” compared to the seasonal flu – and that it is not “mild.” This is compatible with what the CDC is saying, but it is not compatible with the CDC’s own data. Based on the CDC’s November 12 estimates of the number of cases and number of deaths through October 17, the pandemic’s case fatality rate so far is six times lower than the seasonal flu case fatality rate:

- Pandemic: 3,900 deaths divided by 22 million cases = CFR of 0.018%

- Seasonal flu: 36,000 deaths divided by 31 million cases (10% of 308 million population) = CFR of 0.12%

If you look at the CFR separately for people 65 and over versus people under 65, the pandemic’s CFR is a little higher than the seasonal flu CFR for people under 65, and a lot lower than the seasonal flu CFR for people 65 and over. Think in terms of four separate diseases: (1) pandemic flu for under-65s; (2) seasonal flu for under-65s; (3) pandemic flu for 65-and-overs; (4) seasonal flu for 65-and-overs. Then #4 is a killer. By contrast, #s 1, 2, and 3 are all pretty mild – though #2 is a bit milder than #s 1 and 3. That’s the picture the CDC’s data paint. It’s very different from the word picture the CDC is painting, and you propose to paint.

I also don’t like your bald claim that people “still need to get the seasonal vaccine” because we “have yet to move into the peak normal seasonal flu season.” This, too, replicates CDC messaging, but in my judgment it doesn’t live up to your goal of transparency. In past pandemics, the pandemic strain has usually supplanted the previously circulating seasonal strains, becoming the new seasonal strain. The same thing happened in most southern hemisphere countries this time around; Australia and New Zealand, for example, saw very little seasonal flu during their winter season this year. Of course a return of the seasonal strains is likelier if the pandemic ebbs. And even if the pandemic remains, it’s possible that the pandemic and seasonal strains will coexist, at least this season.

Basically, nobody has a clue whether to expect a normal flu season or not. That’s a good enough reason to get the seasonal vaccine, especially for seniors. But you’re no more certain that the seasonal strains will return than you are that the pandemic strain will remain. If you’re going to be transparent about the latter, be transparent about the former too. What you say, in short, should be compatible with the possibility that there may be little or no seasonal flu this year.

Are people apathetic about the environment, or is it something else?

| name: | Cordell Jeffries | |

| Field: | Environmental activist | |

| Date: | November 20, 2009 | |

| Location: | Missouri, U.S. |

comment:

I just read “Watch Out!” and loved it. The problem of apathy has hardly disappeared in the two years since you wrote it.

Eco-apathy is a problem that an organization (http://friendiam.com/) is being created to address. While I would love to talk to you about it in more detail, right now I have a simple-but-hard question to ask.

Has any entity ever credibly computed the number of people on the planet who could be considered apathetic with regard to the environment?

With the number of people with Internet access surpassing one billion people in 2009, as well as an estimated 4.1 billion mobile phones currently on the planet, it would be fascinating to know what the range of answers to that question is. Granted, the information hinges completely on what “defines” environmental apathy.

Any light you can shed on this subject would be appreciated.

Peter responds:

As you say, counting people who are apathetic about environmental issues requires a definition of apathy. There is no obvious boundary between “apathetic” and “interested/concerned” – just a dimension along which environmentalists try to move the public.

Of course there have been opinion surveys on environmental concern at least since the 1960s. The number of people reporting themselves as concerned went up quickly in the early years; it has probably plateaued by now (though I haven’t checked), but at a very high level. Nearly everybody in the developed world (even global warming deniers) claims to be environmentally concerned – and means it; and even can cite behaviors like recycling to prove it. Compare environmental concern with, say, concern about world hunger or HIV or racial justice, and I’m pretty sure you’ll see that environmental concern is more than holding its own.

I realize that this breadth and depth of concern hasn’t been sufficient to motivate the sorts of commitments environmentalists are seeking – for example, willingness to abandon our pursuit of permanent economic “progress” or willingness to make sizable short-term material sacrifices in return for a better environmental prognosis. But calling that problem “apathy” may not be useful. Perhaps it is selfishness, or ignorance, or even ideology (materialism is certainly an ideology, deep-seated in modern consciousness). Perhaps only desperation would motivate the sorts of societal and individual changes many environmentalists now think necessary – and arousing desperation (before it’s too late) isn’t the same as piercing apathy.

An increasing piece of the problem, I think, is denial. If environmentalism requires significant sacrifice of things and values we hold dear, then people may be motivated to eschew environmentalism in order to hang on to those things and values (awhile longer, anyway). That would be desperation itself, not the absence of desperation! And desperation leads to denial.

You might want to read a long column I wrote earlier this year on the ways I think environmental activists may be exacerbating climate change denial in their efforts to fight climate change apathy.

Cordell responds:

Rhetorical concern is easy to quantify, and some results might indicate that apathy (of the 100% pure variety) is “holding its own” at a level one could consider low.

But apathy needs to start being measured in terms of actions, which are also quantifiable. That’s where the proverbial rubber meets the road. And quantification of ecologically motivated action is what I am seeking, even in the form of an educated guesstimate.

Would it be fair to consider raw sales data for less- and non-green products as a somewhat accurate indicator of “action-based” apathy?

If you are wondering where I am going with this train of thought, it is to the simple idea that if every consumer in this consumer culture would purchase the greener version of ONE product in their life from now on, the positive impact on the planet would monumental. And that impact would be multifaceted, one step in the right direction on a litany of eco-issues. I am curious to see if there is a resource for such consumption-driven data.

Peter responds:

I’m not sure how monumental the progress would be if every consumer picked one green product to feel good about buying. The key question, it seems to me, is whether you can help people frame that initial purchase as a behavioral commitment – that is, as evidence that they care about the environment and thus as a foot-in-the-door to more (and deeper) actions in the future.

A lot has been written about the conditions under which people do one thing and then feel free from further obligation (“I gave at the office”) versus the conditions under which people interpret their own initial behavior as just the beginning. To leverage your impact, you will want to read this literature.

Why didn’t President Obama get vaccinated against swine flu? Should he have?

| Name: | David |

| Field: | Public health |

| Date: | November 20, 2009 |

| Location: | Tennessee, U.S. |

comment:

Do you think that President Obama’s decision not to get vaccinated against swine flu was influenced by the backlash that arose following the 1976 swine flu debacle?

Peter responds:

I don’t have any inside information about why President Obama decided not to get vaccinated against swine flu.

But I don’t see how the 1976 swine flu controversy would have led to that decision. It’s true that President Gerald Ford publicized his own swine flu shot in 1976, as part of the launch of the government’s mass vaccination campaign. But Ford wasn’t especially criticized for that. He was criticized for launching the campaign at all – because the vaccine turned out to cause Guillain-Barré syndrome in a small percentage of vaccinees, while the pandemic the vaccine was intended to address never materialized.

This time we’ve actually got a pandemic, albeit a fairly mild one. And while the 2009 H1N1 vaccine may turn out to have problems of its own, it’s very, very unlikely to turn out more dangerous than H1N1 itself.

No, I assume President Obama decided not to get vaccinated for the reason he gave: because the CDC had identified a number of high-priority groups to get first dibs on the vaccine, and the President wasn’t in any of the groups. He didn’t want to be accused of line-jumping.

In terms of the national welfare, that decision makes no sense. We all have a stake in President Obama staying healthy. We don’t really want him laid up with the flu for a week. We certainly don’t want him ending up one of the 30% of hospitalized swine flu patients who had no underlying condition to put them on the CDC’s priority list. Presidents get all kinds of medical attention most of us don’t get … and should.

But the government badly overestimated how much vaccine would be available by now, which has led to lots of public outrage about the inadequate vaccine supply, and lots of complaints about why specific people (from Wall Street bankers to Guantanamo detainees) were slated to get some. I can’t dispute that the President would have taken some flack if he had promoted himself to the head of the line. With vaccine demand so obviously outstripping vaccine supply, it would have been hard for him to sell such a decision as setting a good example for other prospective vaccinees.

The question of whether “important people” should be prioritized for scarce medical treatment is one that has bedeviled ethicists for a long time. If we’re going to privilege the President in that way, what about Senators? Mayors? Cancer surgeons? Cops? Sewage treatment plant managers? A lot of people can make a case that the world shouldn’t have to function without them, even for a week. Contingency plans for a severe pandemic often do prioritize key personnel, aiming to keep them healthy so they can keep society’s overstressed infrastructure going. But with a pandemic this mild, the CDC prioritized only people most at risk, plus those who come into close contact with people most at risk (health care workers and other caretakers of the vulnerable).

Of course if the President comes down with swine flu, he will be criticized for having put public relations ahead of the public’s business.

If he had gotten vaccinated, he’d have been criticized – by pretty much the same people – for jumping the line.

And if he had utilized one of my favorite risk communication strategies and shared the dilemma, asking the public whether he ought to get vaccinated or not, he’d have been criticized for indecisiveness. “No wonder he can’t make up his mind about Afghanistan. He can’t even decide whether to get a flu shot!”

So far he hasn’t been criticized much for going unvaccinated. So as long as he stays healthy, I guess he made the right decision … sort of.

Using DDT against malaria in Africa

| Name: | Happynus Pilula |

| Field: | Student |

| Date: | November 20, 2009 |

| Location: | Tanzania |

comment:

I am interested to know the risk associated with the use of DDT in malaria vector control so as to simplify the risk communication process to the society and stakeholders at large.

Peter responds:

You have three problems here:

- Convincing people to take the risk of malaria seriously enough and to take appropriate precautions against that risk.

- Convincing people not to overreact to the risk of DDT – not to object to its appropriate use against malaria.

- Convincing people to take the risk of DDT seriously enough and to take appropriate precautions against that risk too.

For malaria in general, look at the articles indexed under “Precaution Advocacy (High Hazard, Low Outrage).” Those are the articles focusing on how to convince people to take precautions about a serious risk (like malaria) when the problem is that they are too apathetic about the risk.

Something to keep in mind as you think about malaria precaution advocacy: Especially in developing countries, officials often recommend precautions that are not practical for people to take. Telling people to wash their hands, for example, is frustrating advice in places where clean water is in short supply. Impractical advice undermines the credibility of many health promotion efforts, and it arouses frustration and a sense of futility in the people.

For DDT in particular, the risk communication problem is different and more complicated. As I understand it, DDT is genuinely harmful to the environment, and also genuinely useful against malaria. Other ways of dealing with malaria are less effective and/or more expensive, and thus less practical for developing countries with a serious malaria problem.

Bear in mind that the effectiveness of DDT versus other ways of addressing malaria isn’t a communication question, and you can’t assume I’m right about the answer!

But if I am right, here’s the problem: In richer countries with less serious mosquito-borne diseases – e.g. the U.S. – outlawing DDT made sense. In poorer countries with more serious mosquito-borne diseases – e.g. Tanzania? – outlawing DDT may not make sense. But if DDT is outlawed in the developed world, while DDT manufacturers (also in the developed world) are shipping DDT to developing countries, that arouses all sorts of understandable outrage. Activists in the developed world agitate against the “circle of poison.” People in the developed world may feel guilty. People in the developing world will surely feel envious and discriminated against.

In other words, DDT may make good technical sense in Tanzania’s battle against malaria, but it may arouse so much outrage that the Tanzanian government (not to mention international agencies and donor countries) may find it difficult or even impossible to use because of public resentment.

In this case the problem wouldn’t be too little outrage about malaria, but too much outrage about DDT – which becomes a symbol of Tanzania’s poverty and oppression, and of the double standard of various outsiders (pesticide manufacturers, international agencies, donor nations). Unless the outrage about DDT is managed well, it may be hard to manage the hazard from malaria – and people may die needlessly.

For more on how to handle this sort of situation, see the articles indexed under “Outrage Management (Low Hazard, High Outrage).”

Note that managing DDT outrage well does not mean teaching people (falsely) that DDT risks are trivial. It means teaching people (accurately, I am told) that DDT risks are justified in places where malaria risks are greater and where alternative remedies are more expensive, less effective, or impractical for some other reason. This has to be done sadly, not triumphantly. The message isn’t that people are foolish to worry about DDT, but rather that the malaria situation is dire and Tanzania must make painful choices.

You can see why this is a difficult message to convey – and perhaps impossible for a rich donor nation or a multinational pesticide company to convey. And again I want to stress that it is a sound message only if it is technically accurate; that is, only if it really makes sense for Tanzania to deploy DDT against malaria, given the health, environmental, and economic realities your country faces. That’s a question I am not qualified to judge.

The third problem has to do with minimizing the genuine risks of DDT. If the authorities can manage DDT outrage effectively enough to be able to use the chemical, they will also want to do everything they can to show people what precautions they should take (and what precautions the authorities promise to take) to protect themselves, their families, their animals, and their crops from the DDT.

If people are worried about the DDT, discussing with them what precautions they can take and what precautions the authorities will take is a key aspect of good outrage management. If people are not worried about DDT, then convincing them to take appropriate precautions is, once again, precaution advocacy.

The emerald ash borer: a very tough precaution advocacy problem

| name: | Drew Todd | |

| Field: | State urban forestry coordinator | |

| Date: | October 28, 2009 | |

| Email: | drew.todd@dnr.state.oh.us | |

| Location: | Ohio, U.S. |

comment:

The Emerald Ash Borer (EAB), a non-native insect from Asia, was identified in northwest Ohio in 2003. Since that time, it has spread to over 50 of Ohio’s 88 counties, infesting and killing rural and urban native ash trees. For the past several years, Ohio’s Urban Forestry Program has been helping communities prepare for their inevitable infestation.

We’re attempting to provide awareness and options in hopes that communities would take appropriate and timely action. The environmental and social loss of a community’s public ash trees, which may exceed 10% of its street tree population, pales in comparison to the economic burden of having to remove hundreds of ash trees at the same time.

Many communities have taken our mitigation suggestions, and are systematically removing their ash trees prior to infestation. Unfortunately, many more communities have failed to act. Those communities in northwest Ohio that haven’t proactively removed their ash trees are now requesting our immediate help to convince decision-makers to act.

If possible, we’d like to identify those barriers that inhibit municipal administrators in other parts of our state from failing to take appropriate and timely action. What advice or guidance can you offer to help us overcome this anticipated EAB apathy?

Peter responds:

You’re facing as difficult a precaution advocacy problem as I’ve encountered in some time.

Here’s what you’re up against:

- People discount the future. This is a perennial barrier to many precaution advocacy efforts: It’s hard to persuade people to take action against a problem they don’t face yet. Maybe if the emerald ash borer were advancing inexorably on a specific town in visible ways – three miles away last year, two miles away this year – you might be able to arouse some sense of imminence. But “it’ll get here eventually” isn’t much of a call to arms.

- I’m sorry to say this: Most people are likely to find the EAB issue pretty boring when they hear about it. Getting people to take action against a problem they don’t face yet pretty much requires getting them to imagine the problem. It’s tough enough to get people to imagine a really vivid problem, like a flood or a pandemic, before it’s imminent. Arousing outrage is usually the key to precaution advocacy. But your issue doesn’t have a whole lot of outrage potential. Maybe close-up photos of the EAB can inspire a little dread, or at least a little disgust.

- You have no real precaution to advocate. If I understand you right, you’re not trying to persuade communities to solve their EAB problem by taking prompt action to extirpate the emerald ash borer or protect their ash trees. The problem is unsolvable. The ashes are doomed: ashes to ashes. All you want is for communities to cushion the economic blow of having to remove lots of infested ash trees all at once by preempting the insect and removing the ash trees before they’re infested. Lots of research shows that people are more easily motivated to solve a problem than to mitigate one – especially one they don’t face yet. You’re not offering people ways to prevent the ash borer infestation, not even ways to make it less likely or less unpleasant … just ways to make it less expensive.

- People love their trees, even their publicly owned street trees. But I don’t see any way to harness that love on behalf of your goal of getting communities to kill the trees before they have to. If anything, the love cuts the other way. Imagine trying to persuade people to kill their pets now because they’re going to get sick and die in years to come.

Finally, I’m not convinced that your goal makes sense. You don’t seem to be claiming that the infested ash trees will do actual harm – fall down on cars and pedestrians, for example, or infest other species. You’re just saying that communities can better afford to remove the trees piecemeal than all at once.

But assuming a community waits till the infestation arrives, why will that require it to cut down all its ash trees at the same time? Will they really all get infested the same year? Even if they do, can’t the community take its time removing them? Mightn’t some ash trees withstand the attack and never need to be removed at all? If there really are good reasons why it’ll be necessary to remove all the trees in the same year, why won’t that be cheaper than coming back again and again for more trees? And why can’t a community start putting away money for the job now, but wait to implement until the infestation arrives? Maybe the experts will come up with a solution in the meantime. Even if they don’t, why should the community deprive itself of an amenity prematurely?

There may be good answers to these questions. If so, you need to provide the answers. They’re not obvious on their face, and they’re not in the brief comment you sent me. The burden of proof is on you to convince community leaders and community members that preemptive ash removal is sound policy.

One possible answer: “If we replace our doomed ashes now with saplings of some other species, by the time the EAB hits town we could be well on our way to a new, more resilient canopy of trees.” Another possibility (if it’s true – I’m making up facts here): “Other communities have found it really painful to watch their beloved ashes slowly succumb to the EAB. They’re visibly sick for years before they finally die. It’s less painful in the long run to bite the bullet and replace the trees now.” Or perhaps: “If we cut down healthy trees, they can be used for firewood. If we wait till they’re infested, the wood will be quarantined and will have to be disposed of carefully, expensively, and uselessly instead.”

Still, unless the infested trees are going to do actual harm, I’d be inclined to enjoy my ashes while I can.

Building a policy case for preemptive ash removal is your second task. Your first task is finding a way to gin up some emerald ash borer outrage. It won’t be easy.

There’s an alternative you might want to consider: dilemma-sharing. Instead of trying to sell communities on cutting down their ashes now, make it your goal to warn communities that the EAB is on its way and so far appears unstoppable. Lay out the policy alternatives and the pros and cons of each; describe the reasoning of some communities that have decided on preemptive removal and some other communities that have decided to wait till they have no choice. Define success not in terms of what a community decides to do, but in terms of whether it is aware of the problem and makes a thought-through policy decision (with adequate public awareness and public involvement) on how it wants to proceed.

Among the advantages of this approach: You no longer need to try to arouse more outrage than a neutral, factual description of the situation naturally arouses. With luck (and some skill), the paradox of the risk communication seesaw may come into play. If you’re less committed to persuading people to take action now, they may be likelier to decide that that’s the best option. For sure they’ll be likelier to rely on your information to make their own informed choice.

The meme that this pandemic is “like the seasonal flu”

| name: | Anna Meldolesi | |

| Field: | Science journalist | |

| Date: | October 23, 2009 | |

| Location: | Italy |

comment:

I’m a science journalist working in Italy (www.darwinweb.it). I think the national strategy of communication about pandemic H1N1 in my country is downplaying risks and uncertainties. The claim of the Italian TV advert is: “This pandemic influenza A is a normal flu. It can be best handled by following five rules….”

(If you are interested you can see the TV ad at http://www.wikio.it/video/1796856. ![]() The mouse is a 50-year-old puppet unknown among today’s children. According to the Italian government, 257 TV stations in South America are asking for permission to broadcast the Italian ad.)

The mouse is a 50-year-old puppet unknown among today’s children. According to the Italian government, 257 TV stations in South America are asking for permission to broadcast the Italian ad.)

In my opinion the message becomes: Pandemic flu is equal to seasonal flu and is normal.

Epidemiology says it is not true that pandemic flu is the same as seasonal flu. I don’t know what “normal” means from a scientific point of view, but I guess for laypeople it means you have to do nothing special if something is normal.

I wonder why people should improve hygiene standards and (more important) why they should get their vaccine shots if pandemic influenza H1N1 is normal. Consider that in Italy only 19% of people get vaccinated for seasonal flu every year. Coverage is only 30% among health workers.

May I know your opinion?

Peter responds:

My wife and colleague Jody Lanard collaborated on this response.

We agree with you. Pandemic H1N1 Influenza A is not a normal (that is to say, “average seasonal-type”) flu. Some of the reasons:

- Its epidemiology is radically different so far. The seasonal flu attacks all ages, but roughly 90% of seasonal flu deaths (at least in the U.S.) are 65 or older. The pandemic flu, in stark contrast, infects almost no one over 65, and very few over 50. Meanwhile, people under 65 who catch the pandemic flu have a much higher rate of complications and death than people under 65 have when they catch the (average) seasonal flu strains. And this age difference is even more pronounced when you break the under-65s down into narrower age ranges. In other words, the pandemic so far is much safer than the “normal” flu usually is for the elderly, and significantly more dangerous than the “normal” flu usually is for their children and especially their grandchildren.

- Although we don’t yet know the ultimate attack rate of the pandemic flu virus, far more people are susceptible to it (because they lack any degree of prior immunity) than are susceptible to the seasonal flu strains. However mild or severe the pandemic turns out to be, most flu experts think it will end up more pervasive than the “normal” flu.

- Perhaps most important, the “normal” seasonal flu strains rarely if ever mutate in a way that suddenly causes them to be much more virulent. Pandemic flu viruses have a history of sometimes doing exactly that: mutating to be much more virulent than when they first emerged as a novel virus. Flu is never predictable, but the behavior of pandemic strains is even less predictable than that of seasonal strains.

So all communications that aim to “normalize” the pandemic to create the impression that it is “like the seasonal flu” are misleading, unless they also vividly dramatize the ways in which the pandemic and seasonal strains are different. Sometimes the misleading communications come from sources who don’t know they are misleading – local health officials or journalists who haven’t studied influenza or perused the relevant government statistics. But when the meme that the pandemic is “like the seasonal flu” comes from influenza experts who are compiling those government statistics, the communication is intended to mislead.

More often than not, the purpose of the misleading normalizing meme is to avoid frighening the public. We have written extensively about public health officials’ undue fear of public fear. (See “Fear of Fear: The Role of Fear in Preparedness … and Why It Terrifies Officials.”) When this type of over-reassurance is combined with efforts to get the public to take more than the usual precautions, it is a mixed message, likely to backfire in predictable ways:

- Some people who believe the reassuring half of the message will see no reason in take the precautions. (This is the outcome your comment focuses on.)

- Others will discount the reassuring half of the message, thereby losing some trust in the officials who issued the message – but will take the precautions.

- And still others will distrust both halves of the message, and seek unofficial sources of information in order to decide what to do. And we all know the range of unofficial sources that are out there in Blogville.

Other times – even more culpably – the purpose of misleading over-reassurance is to reduce the public’s demand for unavailable resources for coping with the problem at hand. For instance, public health officials in India routinely over-reassure their publics about various outbreaks for which they have inadequate vaccine or antibiotic supplies.

Regardless of why Italian officials are trying to convey the misimpression that the pandemic virus is just like a “normal” flu, it is bad risk communication. It will ultimately contribute to increased (and justified) mistrust of public health officials.

By the way, the public service announcement you link to also makes the misleading – but ridiculously common – assertion that the most important thing people can do to reduce their risk of catching the flu is to wash their hands. This message, too, is part of a pattern of over-reassurance. There is very little research evidence to support the notion that flu is significantly transmitted by virus on people’s hands, or that frequent hand-washing materially reduces flu risk.

Mandatory vaccination for health care workers

| name: | Ashley Conway | |

| Field: | Public health nurse | |

| Date: | October 23, 2009 | |

| Location: | New Jersey, U.S. |

comment:

Thank you for the September communication update on pandemic influenza. It was, as always, useful and insightful.

I am interested in knowing your thoughts about the New York State Health Department’s emergency regulation requiring seasonal and H1N1 influenza immunization for certain health care workers. Also, given your opinion about the questionable emphasis on seasonal flu vaccination, how you think the seasonal vaccine “shortage” impacts risk communication in the pandemic.

Peter responds:

Jody Lanard and I are firmly convinced that health care workers with patient contact should be vaccinated against both the pandemic flu and the seasonal flu. This isn’t just for the sake of their own health. It also helps protect patient health; people sick from other causes shouldn’t have their illness unnecessarily exacerbated by flu. And it helps reduce absenteeism at a time when the demands on hospitals and other health care workplaces are likely to be even greater than usual.

Given that employers, patients, and the public have a stake in the vaccination of health care workers, there is a pretty decent legal and ethical case for making vaccination mandatory.

Nonetheless, we’re against it. As risk communication consultants, we know that control is one of the most powerful of the outrage components. ![]() Coercion arouses outrage even when the coerced behavior itself doesn’t. And when the coerced behavior is something as personally upsetting as a medical intervention you have decided you don’t want, the outrage is likely to be extremely high. The resulting stress on health care workers’ morale, on labor-management relations, and on patient-provider relations is an awfully high price to pay.

Coercion arouses outrage even when the coerced behavior itself doesn’t. And when the coerced behavior is something as personally upsetting as a medical intervention you have decided you don’t want, the outrage is likely to be extremely high. The resulting stress on health care workers’ morale, on labor-management relations, and on patient-provider relations is an awfully high price to pay.

Moreover, mandatory vaccination will almost certainly increase the number of vaccinees who suspect that their future health problems are side-effects of the vaccine. An employer (or a government) that compels health care workers to get vaccinated can expect to face litigation not just about the legitimacy of the compulsion but also about specific health impacts attributed to the vaccine.

In “Talking about H1N1 Vaccination,” I argued that overselling flu vaccination was bound to backfire by arousing more outrage, more skepticism and resentment, and more psychogenic illness. The same is true – in spades – of requiring flu vaccination.

It’s not as if we were talking about a few idiosyncratic holdouts. In survey after survey, everywhere in the world, large percentages of health care workers have voiced their reluctance to get either flu shot. Though many health care workers have misunderstandings about flu and the flu vaccine (which they often communicate to patients), health care workers obviously are better informed and more experienced with regard to flu vaccination than the general public; and they have more reasons to get vaccinated than the general public. So it’s a very bad sign that flu vaccination proponents have failed to make their case in the minds of this crucial target audience.

The solution isn’t coercion. The solution is to figure out what vaccination proponents are doing wrong when they try to make their case. For at least part of the answer, see “Convincing Health Care Workers to Get a Flu Shot … Without the Hype.”

Ethicist George J. Annas recently wrote an excellent Newsday op-ed on this topic, “Don’t force medical pros to get H1N1 vaccine.” Annas’s op-ed helped persuade “revere” (the pseudonymous editor of the “Effect Measure” public health blog) to change his mind on the question. His October 5 post about why is worth reading, as are the comments that follow.

You also ask about the temporary shortage of seasonal flu vaccine in some places. As I’m sure you know, the seasonal flu vaccination campaign in the U.S. was pushed forward this year in hopes of getting it partly out of the way before the pandemic vaccination campaign got into gear. At the same time, the U.S. government asked manufacturers to interrupt their seasonal vaccine run in order to make pandemic vaccine, before completing seasonal vaccine production. So the early demand for seasonal vaccine (created by the government push) is outstripping the early supply in some places – though health officials are fairly sure that the supply will catch up, and in the end will probably exceed the demand as always.

In places where people are upset about the temporary shortage of seasonal flu vaccine, their worry and irritation should be validated as understandable. Public health officials should acknowledge their role in the shortage: They started early urging people to go get the seasonal vaccine, leading to some frustration when people tried to comply and found that there wasn’t enough vaccine for them yet because manufacturers were busy making pandemic vaccine instead.

Officials, especially local officials, should also emphasize much more frequently that so far there is almost no seasonal flu circulating in the U.S. So there is probably ample time to wait for the additional supply that’s coming.

And then officials should go further, acknowledging that there may be very little seasonal flu in the U.S. this year at all. If the pandemic H1N1 strain continues to circulate widely, it may out-compete and largely supplant the seasonal strains in our winter, as it did in most southern hemisphere countries during their winter. Officials are understandably reluctant to acknowledge this possibility, because they don’t want to discourage people from getting the seasonal vaccine. But the credibility of vaccination promotion – already in deep trouble – cannot afford the additional damage that will result if an aggressive seasonal vaccination campaign is followed by virtually no flu season at all, and officials are forced to concede belatedly that they always knew that was a distinct possibility.

The priority groups for seasonal vaccination and the priority groups for pandemic vaccination are different but overlapping. Health care workers are a priority group for both. So it makes sense to urge health care workers to get vaccinated as soon as they can with whichever vaccine is locally available first, and then to get the other one when it becomes available to them. And for health care workers who are reluctant to get both vaccines but willing to consider getting one or the other, it makes sense at this point to urge them to get the pandemic vaccine, since that helps protect against the flu virus that is widely circulating in the U.S. right now.

“Urge” – with evidence; with appeals to altruism and professionalism as well as self-interest; and with empathic acknowledgment of their concerns, their reservations, and their skepticism. Not require.

Research to prove that outrage management works

| name: | Andrew Macalister | |

| Field: | Communications consultant | |

| Date: | September 5, 2009 | |

| Location: | New Zealand |

comment:

I am interested to know if any research has been done to quantify changes in attitudes of members of the public to an outrage management situation, following the application of your risk communication principles – or some such “empirical” demonstration of the value of applying these risk communication principles.

Here is the background to my question:

New Zealand has a classic low hazard/high outrage debate that has been rumbling on for years – the aerial application of sodium monofluoroacetate (known as 1080) for pest control. A quick Google search will show up the tenor of the debate.

From 2002–2007 I was contracted by one of the two major 1080 users to establish a public consultation model for the aerial 1080 operations, in response to significant public opposition and operational delays. In doing so, I drew heavily on your risk communication principles.

With the consultation process in place in 2004, aerial operations were able to be planned and implemented on time, with the backlog cleared by 2005–06. In fact, only one operation between 2004 and 2007 generated strong public opposition. This was in stark contrast to the situation before I became involved, which was very inflamed.

During this time, I ended up managing the entire programme from 2005–2007. I resigned at the end of 2007 to resume some other projects, and unfortunately, since then, all the principles we put in place appear to have become eroded. Last year, the aerial programme erupted in a storm of acrimony and threats that hadn’t been seen since 2003.

I have the opportunity to put some research proposals up to my former client and, in the context of the above, believe it would be worth trying to set up a research project where we can tangibly demonstrate the value of good risk communication – such as by measuring attitudinal change before and after a risk communication intervention. I have talked to a couple of social scientists but am still struggling to define how we might set up such a research project. Hence my question – is there some existing research model that has been implemented in the past, which we could draw on?

Peter responds:

The “outrage factors” ![]() that lead people to experience a situation as high- or low-risk regardless of the actual hazard have been well-documented in research going back to the 1970s, especially the so-called “psychometric” research of Paul Slovic and colleagues. There are endless debates over how to measure the various factors. And it’s far from obvious how to combine them into a composite variable called “outrage” (or even whether it makes sense to do so). But nobody disputes that control, fairness, trust, dread, and the rest significantly affect the way people see risk. You can choose among a wide range of ways to measure these factors.

that lead people to experience a situation as high- or low-risk regardless of the actual hazard have been well-documented in research going back to the 1970s, especially the so-called “psychometric” research of Paul Slovic and colleagues. There are endless debates over how to measure the various factors. And it’s far from obvious how to combine them into a composite variable called “outrage” (or even whether it makes sense to do so). But nobody disputes that control, fairness, trust, dread, and the rest significantly affect the way people see risk. You can choose among a wide range of ways to measure these factors.

When we talk about measuring outrage, we can mean at least four different things.

- We can try to measure the outrage-provoking potential of the situation itself – the extent to which your organization shares control, acts fairly, builds trust, etc., and the extent to which it has done so in the past. This is the main focus of my “OUTRAGE Prediction & Management” software, for example (now downloadable without charge).

- We can try to measure people’s experience of the situation – the extent to which your stakeholders feel they have some control, are being treated fairly, can trust you to do the right thing, etc. This is what psychometric research does.

- We can try to measure the emotions and risk perceptions that these various outrage factors lead to – how frightened or angry people say they are, or how dangerous they say the situation is. These are often the outcome variables in social science research about risk.

- We can try to measure the behaviors that make outrage manifest – how many people join opposition organizations, sign petitions, participate in demonstrations, and the like. These are often the main concern of clients, but ideally outrage management aims to deter these behaviors rather than merely responding to them.

There has been much less research on what you want to study: the effectiveness of outrage management strategies ![]() . How is people’s outrage (in any or all of the four meanings listed above) affected by things like acknowledging your organization’s prior misbehavior and sharing control over how the situation is handled?

. How is people’s outrage (in any or all of the four meanings listed above) affected by things like acknowledging your organization’s prior misbehavior and sharing control over how the situation is handled?

To test the impact of various outrage management strategies you have to measure the outrage, of course. But that’s not the main problem.

The main problem is randomization. To find out how well various outrage management strategies work, you’d want to start out with lots of people facing some low-hazard, high-outrage risk controversy. You’d assign them randomly to receive different messages (apologetic or stonewalling, transparent or secretive, etc.), and then you’d see which groups ended up more or less outraged. Better yet, you’d have lots of different communities facing the same controversy, and you’d randomize them and treat them differently; that way you could explore the resulting group dynamics, not just individual reactions.

For obvious reasons, nobody does that. In the real world, it’s extremely difficult to randomize individuals – not to mention trying to randomize outraged individuals. It’s basically impossible to randomize communities, outraged or not. And no client would let you do it anyway. If you think stakeholders will calm down if you do X and get even more outraged if you do Y, your client isn’t about to authorize you to do X to half of them and Y to the other half in order to find out if you’re right.

So you’re left with three main research alternatives, none of them ideal.

Case studies.

Your comment mentions that you tried a combination of outrage management strategies with regard to aerial pesticide spraying in New Zealand, and together they worked pretty well. Then someone else took over, changed strategies, and stakeholder outrage went up. That’s a case study. It’s evidence – only anecdotal evidence, but evidence nonetheless. If some neutral third party were watching instead of you, it would be better evidence, less vulnerable to your bias that your way works best. But it would still be just an example, with no way to determine which of the things you did made the difference, or whether your outcome was typical or unique.

Despite the evidentiary weaknesses of case studies, most people find them persuasive – often more persuasive than rigorous quantitative proof. (Consider how a couple of neighborhood cancer stories can overpower a stack of epidemiology and toxicology reports.) In general, people learn best from their own successes and other people’s failures: “We did this and it worked. They did that and it backfired.” Learning from your own failures is tougher.

Case studies of outrage management failures are easy to find. When a community explodes in outrage, journalists will be there to cover the controversy, providing a rich (though not necessarily unbiased) source of data about what went wrong and why. Case studies of outrage management successes are much scarcer. Reporters don’t usually write stories about why people aren’t upset. And an organization that has done a good job of calming its stakeholders will rightly think twice before writing up its success, lest people feel manipulated and end up outraged about the successful effort to minimize their outrage. But there are some academic case studies available of good public engagement efforts regarding various controversies.

Focus groups and surveys.

A food industry client of mine has had several recalls in recent years, one of them serious. Consumer awareness of the recalls is high, as is food safety concern; some consumers have stuck with the company’s products anyway and some haven’t. The company needs to know how both groups feel about the company, its products, and its recalls; how they would react if there were yet another recall; and above all what they think of various food safety measures and messages the company is considering.

The best way to answer these questions is a series of focus groups, perhaps followed by a survey. Focus groups provide richer data, while surveys (with a random sample of the population of interest) provide more reliable data. So you use the former to suggest hypotheses and the latter to confirm them.

When it comes to testing possible outrage management approaches, survey methodology can be unwieldy, so organizations often rely on focus groups alone, figuring that if several focus groups have pretty much the same reaction, that’s the reaction you’d expect in a survey (and in the real world) as well. The trick is to make sure you’re testing your outrage management strategies in a realistic context. If you simply ask people which message they like better in the abstract, the one where you say everything’s fine or the one where you admit some screw-ups and promise to do better, a lot of them are probably going to prefer to be told that everything’s fine. But if you test the same two messages in the context of a “radio newscast” that quotes a range of sources, you’ll get a different response. Since the newscast covers other people talking about what you did wrong, the focus group is likely to respond better when you’re admitting the problem than when you’re denying or ignoring it.

Like case studies of successful campaigns, organizations’ focus groups are virtually always proprietary. Usually their surveys are too. And when organizations do intend to make their surveys public, they tend to ask different questions (and ask them differently), collecting ammunition rather than guidance.

Even surveys aren’t true experiments. You’re asking people how they responded when X happened, or you’re asking them how they think they would respond if X happened. That’s very different from making X happen to some randomly assigned people but not to others and watching how they actually respond.

-

Simulation experiments.

Although real-world outrage management experiments are unfeasible, if you’re willing to forgo the real world you can do a real experiment. Typical is a study I conducted in 1990 (back when I was an academic) with Paul Miller and Branden B. Johnson. We wrote hypothetical news stories about a perchloroethylene spill, systematically varying three factors: (a) the technical seriousness of the spill (the hazard); (b) the amount of technical information in the news story; and (c) the outrage in the news story – whether the government agency handling the cleanup sounded responsive or unresponsive, sympathetic or contemptuous, etc., and whether neighbors sounded frightened and angry or calm and impressed. Then we went door-to-door, asking people to read one story (chosen at random) and tell us how they felt about the spill. Our analysis was able to show that the outrage in the news stories affected people’s hazard perception more than five orders of magnitude of actual hazard.

For the details of this study and two others, see “Agency Communication, Community Outrage, and Perception of Risk: Three Simulation Experiments.” See also this index of some of my other research on outrage management.

From time to time risk communication scholars have done their own studies to test some of my outrage management principles and recommendations – sometimes with my involvement and sometimes without it. If you’re interested, check out the work of Lars-Erik Warg, Kjell Andersson, and colleagues at Örebro University (warning: most of it is in Swedish). Kenneth Lachlan and Patric Spence have also published several papers together (in English) on how to measure outrage and outrage management – see for example “Measuring Sandman’s Hazard and Outrage Model in Multiple Contexts.” I have some problems with how Lachlan and Spence define and operationalize my concepts, but probably I’m not the best judge of that.

There have been other outrage management studies over the years. Try searching in Google Scholar for Sandman + outrage + measurement.

A few years ago, Rob Folger at the University of Central Florida business school launched some research aimed at documenting whether companies could reduce stakeholder outrage by following my recommendations. I haven’t seen any publications yet – but you might want to contact him about his methodology (and why he gave up, if he did).

When they forgo real-world testing, simulation experiments forgo something else as well: the societal context. If you go door-to-door asking about hypothetical news stories, you can get a pretty decent idea of how isolated individuals tend to respond to news about a risk controversy. That’s on target for, say, a food manufacturer that has been through a few recalls. But in a hot local controversy, it’s not usually the response of isolated individuals that matters most. It’s the response of networked stakeholders – especially those who have gotten involved, gone to a few meetings, listened to the activists, and thought about becoming activists themselves. What does it take to get somebody like that to give you another chance? That’s probably the single most important outrage management question. Simulation experiments can’t answer it, nor can focus groups and surveys. You’re back to case studies.

Andrew responds:

Thanks very much for your reply. It has helped to clarify my own thinking on this.

Ultimately, I agree that real-world case studies which have not elicited negative behavioural responses would be the most persuasive argument for an outrage management strategy.

In a research context, however, it seems that a focus group approach before and after a real-world operation would be most useful. It is not a true experiment, but neither is most of the related field research undertaken in New Zealand in relation to the use of 1080. Conducting a focus group with willing participants from the affected community, and perhaps supplementing that with a small survey after the operation, would be relatively straightforward.

However, the additional problem I foresee is that in order to obtain the same participation before the operation commences, we would effectively be letting the cat out of the bag by alerting the respondents of the forthcoming operation in their area. That is unlikely to be acceptable to the agency.

Yet if we waited until the agency had made its initial advice of the operation, or even made the request for respondents’ input simultaneously, then I would feel that the baseline information was not truly valid. It would not be an accurate gauge of respondents’ attitudes before the operation, given that initial contact is so critical to shaping the response of the affected community.

Peter responds:

You’re right, of course, that focus groups and surveys have a Heisenberg effect: The measurement effort changes the thing you’re trying to measure.

It might make sense to use a panel approach – recurring focus groups with the same people. In a pre-1080 panel, you’d raise a variety of environmental issues, and ask generically how people think agencies ought to approach communities about controversial projects. The possibility of your someday using 1080 in the community would be just one of many items discussed, and unlikely to constitute a premature heads-up to the community.

Then, at about the same time as your first public contact about 1080 spraying, you’d reconvene the panel and get its early reactions. At the same time, you’d set up some additional focus groups with new people, as a control against the possibility that the panel had been sensitized and was therefore reacting differently than others in the community. As time went on, you’d continue to dialogue with your panel, and also to convene new groups.

This isn’t perfect either. For one thing, you'd need to be careful not to say anything in your first session with the panel that its members could see as misleading in hindsight. Maybe you should tell them straight out at the first session that you're considering a project that may be controversial, and that if it’s launched you’ll be seeking their counsel throughout the project – but this first session is to get broad answers to broad questions and you can’t reveal what the project is about until a later, more focused session.

Healthcare reform outrage

| Name: | Brad Ross |

| Field: | Corporate manager |

| Date: | August 31, 2009 |

| Location: | Arizona, U.S. |

comment:

It seems that the people in charge of developing the country’s healthcare policies and laws have done a great job of creating outrage. I see so many of the issues you talk about in this debate/debacle. Seems like the first thing all of the politicians should do is bring you in to teach them a thing or two about outrage management.

Perhaps they could start by saying they are sorry that they fouled up the process. Then they should think about the outrage factors such as control, fairness, process, and dread to change the way the debate is being managed.

Any chance you are getting involved in this to help the process along? I think we need your help.

Peter responds:

I agree with you that an outrage management perspective could have helped – and could still help – to get a decent healthcare reform bill passed. And I think your suggestion to start with an apology for having mishandled the debate is excellent!

I wish I could get involved – even though I’m awfully busy with pandemic communication right now. But no, nobody in the administration (or anywhere else) has approached me about this issue. Other than my recent Guestbook entry on the healthcare “town hall meetings,” I haven’t worked on it at all.

Empathy, Les Havens, and Elvin Semrad

| Name: | David Mobley |

| Field: | Project Director, Elvin Semrad Archive |

| Date: | August 29, 2009 |

| Email: | DMobley184@comcast.net |

| Location: | Massachusetts, U.S. |

comment:

With regard to your excellent article on empathy and its afterword by your wife in 2007, there is a wonderful cassette tape still around in which Les Havens expresses with great compassion what Semrad had taught him. (Originally it was to do with helping in extremis suicidal patients to want to survive.)

OED traces “to share” back to the shearing of sheep – that is to say, taking action which lightens the load to the benefit of both parties. All the accumulated worries and fears which so burden a person invite frustration, rage and hate. The caregiver has to demonstrate a vivid, deep contact with all that, before the other person can experience some measure of relief that he is not alone with it, it can be “sheared.” In some cases this involves dramatics, in other cases a deft touch of perspective.

I think Les would enjoy very much many of your phrasings of volatile situations because the right performative has remained a staple of his style. The former student of Dr. Havens, Elissa Ely, continues his good work in her commentaries with NPR and the Boston Globe.

Peter responds:

Thank you for the wonderful connection between “sharing” and “shearing.”

You wrote to this Guestbook once before after my wife Jody Lanard and I mentioned Elvin Semrad in a website column on “Talking about Dead Bodies.” The “Empathy in Risk Communication“ column never mentions Semrad, but leans heavily on his former student, Leston Havens.

Your comment that “Les would enjoy very much many of your phrasings of volatile situations because the right performative has remained a staple of his style” is particularly heart-warming to Jody, who is a former student of Dr. Havens (and a psychiatry residency-mate of Elissa Ely). Out of shyness, Jody missed several chances to show Les the impact his teaching has had on our work. It is wonderful to get indirect validation from you.

We would love to listen to the Havens/Semrad tape, if you have a copy you could send us.

Agricultural risk communication and human health

| Name: | Amy Delgado |

| Field: | Veterinary epidemiologist |

| Date: | August 29, 2009 |

| Email: | Amy.delgado@iica.int |

| Location: | Costa Rica |

comment:

I have greatly enjoyed and valued your comments on risk communication and disease control and prevention, and I have found them to be incredibly useful in many settings. However, one area that I would love to hear your thoughts on is communicating with the agricultural producer.

Perhaps this falls under the area of segmenting your audience, but I feel that this is a group that is consistently under-targeted or poorly targeted in official communication efforts. Unfortunately, this is a group whose participation, voluntary or otherwise, is usually essential to effective disease detection and control. With so many diseases able to transmit between people and animals, agricultural producers are often the front line of our detection and defense systems. In addition, they often bear the brunt of the expense for disease mitigation measures simply for the “common good,” with little or no financial benefits.

As an example, the swine flu pandemic cost U.S. swine producers millions of dollars and decimated the swine industry in many countries simply because the name “swine flu” was circulated early on, despite no evidence of a link with swine or pork. Now as our curiosity regarding the source and spread of influenza viruses takes a new direction, it will not be long before agricultural health agencies are asking producers to accept disease surveillance programs, enhanced biosecurity requirements, and possibly increased testing requirements for the “safety” of their products.

How do you feel that the communication messages for this group should differ from those for the general public (keeping in mind that they are the general public as well, since they still have to make decisions about what they eat)? Have you been involved in any efforts to develop or plan communication strategies for this audience? Many thanks!

Peter responds:

Your comment addresses how officials communicate with agricultural producers. Your real concern, if I’m reading you right, is how human health officials communicate with owners of farms and agricultural companies.

After I address your issue, I can’t resist turning the tables. You’re unhappy about the way human health officials address agricultural concerns. I take your point. But I’m at least as unhappy about the way farm organizations and agricultural agencies address human health concerns.

When human health people talk about agriculture

As you suggest, the connections between human health and agriculture are becoming more and more obvious, more and more politically loaded, and more and more burdensome on agricultural producers. The main connection of interest used to be foodborne illnesses – and that issue, too, is hotter today than it has been for some years. But we have also entered a new age of infectious diseases. Since many of the highest-profile infectious diseases (including bird flu and swine flu) are transmissible between animals and humans, and since some lower-profile animal-to-human diseases are prevalent (salmonella, campylobacter) or on the rise (Listeria), a whole new cast of characters is paying attention to farm practices … and asking for a variety of agricultural changes aimed at protecting human health.

Your contention is that the health officials pursuing these changes need the cooperation (“voluntary or otherwise,” as you say) of agricultural producers. But, you say, they’re not communicating well with agricultural producers. They’re not talking to farmers enough; they’re not listening to farmers enough; when they do talk or listen, they’re not doing so empathically enough.

Although I haven’t made a thorough study of how health officials communicate about agriculture and how they communicate with farmers, I think you’re almost certainly right. One sign that you’re right is the systematically scanty communication between health agencies and agricultural agencies, even within the same government, about pandemic influenza. My wife Jody Lanard and I have given a large number of pandemic communication seminars (usually separately). The health department sponsoring the event rarely invites participants from its sister agriculture department, even when we have vehemently urged that ag officials be invited. When there is an ag person in the room, he or she is usually the only ag person in the room – and his or her comments often have an understandably beleaguered tone.

If health department communicators aren’t in frequent contact with ag department communicators, and if health department technical people aren’t in frequent contact with ag department technical people, what are the odds that health department messaging aimed at farmers is going to show a decent understanding of what those farmers are up against? And what are the odds that health department recommendations about agricultural practices will be actionable, or that farmers will be inclined to act on them?

So you end up (for example) with public health campaigns requiring farmers in rural Asian villages with nearby bird flu outbreaks to exterminate their healthy flocks, without acknowledging that this constitutes an economic disaster for the farmers and the villages. As I wrote in a December 2006 Guestbook answer:

My wife Jody Lanard and I have done some work (Jody more than I) with international agencies and Asian governments wishing to encourage farmers to cooperate with culls. They often try to claim that an H5N1 outbreak is a serious threat to the health of the farmer and his family. This is simply false. Bird-to-human transmission of H5N1 remains difficult; only a few hundred cases have cropped up in the face of millions of opportunities. Interacting with sick birds is nowhere near as dangerous to the farmer as losing his livelihood. And of course there is no “business case” whatever for a farmer whose birds are healthy to destroy his own livelihood in order to create a cordon sanitaire and stop the spread of infection. That’s wise for the world at large, for reasons of poultry industry prosperity as well as pandemic prevention. But it is surely a net loss – a catastrophe, in fact – for the farmer, his family, and his village. We have advised clients to say exactly that. (It’s not a secret; claims to the contrary are transparently false.) Of course what makes most sense is for the developed world to subsidize compensation to developing world farmers, whose sacrifice helps to protect us all. If compensation isn’t in the cards, there are two other options: appeals to altruism and coercion. Dishonest claims that the farmer ought to want to cull his flock undermine altruism and add insult to the injury of coercion.

Consider in this context the recent discovery in Chile that turkeys can catch the human pandemic H1N1 swine flu virus, and the evidence from Manitoba that pigs (unsurprisingly) catch that virus quite easily (from humans or from each other). In humans, pandemic H1N1 swine flu spreads easily but is very mild (so far). Panzootic H5N1 bird flu, on the other hand, is incredibly deadly to humans, but only rarely spreads from birds to people, and almost never spreads from one person to another (so far). Every epidemiologist’s nightmare is a reassortment of the highly lethal H5N1 virus with the currently pandemic H1N1 virus, which could potentially produce a new pandemic virus with the transmissibility of swine flu and the virulence of bird flu.

So we really don’t want any human, bird, or pig to have both diseases at the same time – and if that does happen we want to know about it as fast as possible, so we can take appropriate steps to reduce the odds that a reassorted virus (if there is one) could escape. We may be entering a period in which bird flu is widespread in birds and sometimes infects pigs and humans, while swine flu is widespread in pigs and humans and sometimes infects birds. If so, we will need the best communications we can manage between public health officials and agricultural producers – worldwide.

Profoundly unempathic bird flu risk communication in Asian villages helped sensitize me to the problem of health officials who either don’t understand or don’t acknowledge agricultural realities. I haven’t paid as much attention as I should to the same problem in the developed world, including the U.S. Even for me, health risk communication and agricultural risk communication have been in separate silos. I will try to do better.

When agriculture people talk about human health

Now let me turn the tables. I have been working for several decades trying to help both industry and government improve their understanding of risk communication principles. Some industries and some arms of government have tended to be quick learners. Others have lagged behind. Agriculture has consistently been among the laggards.

Here are just three of my complaints about how agriculture people talk about human health risk. I welcome your response – and the response of other readers – and maybe eventually I will write something longer (and more thought-through) on agricultural risk communication.

Food safety communication.